1st Feb 2024

A well-oiled machine: We track the remarkable relationship between watches and motorsport

by Watch Collecting

There is barely any other sport in existence so reliant on absolute precision in its timekeeping than motor racing.

If we take that melting pot of perfectionism, Formula 1, as an example, the difference between a good lap and a disaster can be as little as half a second and entire 190-mile races have been decided on gaps measured in the hundredths. That demand for split-second accuracy has been the catalyst for countless innovations in horology through the years, with the automobile and the wristwatch both really coming into being at the start of the 20th century and, in many ways, developing in tandem ever since.

Rolex's title sponsorship of Formula One highlights the close relationship between the watch and motorsport worlds.

Advances in one in terms of manufacturing techniques, revolutionary materials and progressive design, more often than not eventually filter through to the other. Today, car making and watchmaking are two of the biggest industries in the world. Additionally, there has always been a significant commonality between their respective enthusiasts; watch fans are frequently also car fans and vice versa, each delighting in and held spellbound by the engineering marvels evident in both disciplines.

It is little wonder, then, that these two pinnacles of excellence should regularly choose to team up. It is a rare motor race indeed, bereft of watch sponsorships, with the likes of Chopard behind the fabled Mille Miglia endurance event, TAG Heuer taking on timekeeper duties for the Indy 500 and Rolex fulfilling that calling for Formula 1 among many others. In return, watch manufactures are keen to leverage their implied association to the high octane thrills and glamorous environs of the race track by bringing out collaborative models steeped in the styling attributes of famous marques.

Where it All Began

If there is one brand we can look to for some of the most important initial breakthroughs in sports timing in general, it is Heuer. As far back as the late 19th century, their work on simplifying and improving chronograph stopwatches was so far ahead of its time that some of their inventions, such as the oscillating pinion from 1887, are still used today.

By 1911 when the brand unveiled the first ever dashboard timer, the “Time of Trip”, Heuer was synonymous with motor racing. With its running seconds sub-dial complementing the main display it could be used to keep track of a journey’s duration, and its success led to other timers with names which would later be repurposed onto legendary wristwatches of the ‘60s and beyond; the Monaco and Autavia. Ever in search of the ultimate in precision, Heuer would also go on to develop the first ever stopwatch capable of timing down to 1/10th second (the Mikrograph) in 1916, followed by the Semikrograph, accurate to 1/50th second and with a split second function.

They didn’t, of course, have the field entirely to themselves. Rolex, whose watchmaking ability is matched only by their marketing acumen, were quick to align themselves with some of the pioneering figures of motor racing’s first golden age. Sir Malcom Campbell became an honorary “testimonee” when he wore a Rolex Oyster during his land speed record attempts in 1935 on the Bonneville salt flats.

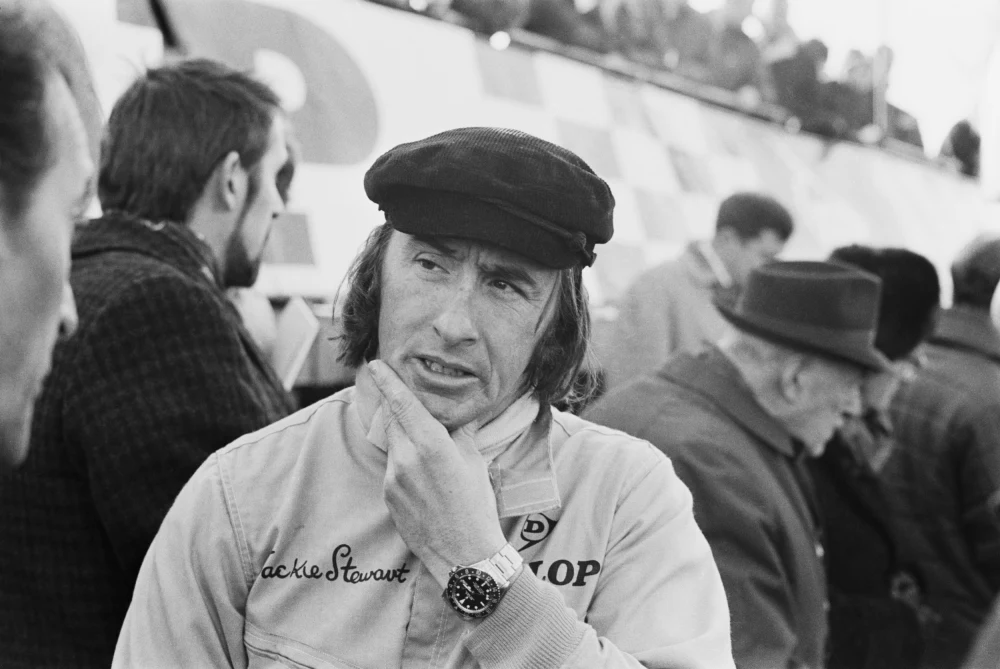

Sir Jackie Stewart wearing a Rolex GMT-Master. One of many watches from The Crown spotted on the wrist of the racing legend.

Another legend of the track, the ‘Flying Scotsman’ Sir Jackie Stewart, has been an ambassador for the manufacture for nearly 50-years, and others, such as Mark Webber and Nico Rosberg, have continued the association into the modern age. But perhaps the most famous Rolex watch; in fact, possibly the most famous sports watch of all time, shares its name not with a driver but with a circuit itself.

The Greatest Drivers’ Watches of All Time

Rolex’s partnership with the Daytona International Speedway dates all the way back to 1963. That was also the year they released a chronograph model of the same name, the Daytona Cosmograph, which would—protractedly—go on to become one of the most in-demand and desirable watches ever made.

A 1960's Rolex Daytona reference 6241 "Paul Newman". Part of Watch Collecting's Motorsport Collection.

Yet, it would take more than a quarter of a century before that turnaround started. First generation Daytonas lingered on the shelves for years, their appeal hampered by their manually-wound movements. By the 1960s, an automatic calibre was the least the watch-buying public had come to expect (thanks to Rolex’s own invention of the Perpetual movement, ironically enough). On top of that, the first inklings of quartz technology were coming through and so a watch you had to remember to wind yourself everyday was a relic from the dark ages.

If people wanted a manually-winding mechanical chronograph, there was already the perfect one on the market built by Rolex’s biggest competitor; the Omega Speedmaster. The Speedy was the first of its type to move its tachymeter scale to the bezel rather than having it printed around the edge of the dial, thus freeing up more space and giving the watch superb legibility. In another ironic episode, Omega had given the Speedmaster its name as it had been designed as the ultimate racers’ companion, whereas Rolex had chosen Cosmograph for the Daytona to give it interstellar ambitions, reasoning that the newly-formed NASA would be on the hunt for an official timepiece for their astronauts. As it turned out, the space agency opted for the Speedy (so granting Omega the greatest advertising bonanza before or since) while the Daytona went on to become the last word in motorsport.

A limited edition 2004 Omega Speedmaster Professional "Japan Racing". Part of Watch Collecting's Motorsport Collection.

But Heuer were certainly not done yet. In 1969, as part of the Chronomatic Group consortium, they developed the Caliber 11, one of the winners of the three-horse race to build the very first automatic chronograph movement.

Heuer put it to work immediately inside new versions of the Autavia, along with two others. The Carrera, another watch named after a world-renowned motor race, was another radical new piece with a familiar name which would get a much-needed publicity boost of its own. The square-cased Monaco found fame on the wrist of ‘King of Cool’ Steve McQueen in the 1971 movie, Le Mans. Playing pro driver Michael Delaney, McQueen somehow managed to contrive a full 15-minutes of screentime for the Monaco, putting the watch on the map and Heuer in the black.

Screen legend Steve McQueen rocking a Heuer Monaco in the film, 'Le Mans'

Yet, that little touch of Hollywood glitter was nothing compared to that sprinkled on the Daytona. When the icon that is Paul Newman was pictured wearing his older, manually-winding ref. 6239 frequently in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it skyrocketed interest in the model at the same time as the second generation, automatic versions were coming to the fore. Before long, demand for both was unlike anything the industry had ever witnessed.

Watches in Motorsport Today

Possibly buoyed by that level of desire, there are an abundance of partnerships between watchmakers and both motor racing teams, as well as individual drivers today. Most prominently, avant-garde manufacture Richard Mille currently sponsors two F1 teams, having taken over from Hublot at Scuderia Ferrari in 2021 and signing a 10-year agreement with McLaren Automotive in 2017.

A 2016 Richard Mille RM005 'Felipe Massa'. 1 of just 300 examples and part of Watch Collecting's Motorsport Collection.

The association has produced some extraordinary timepieces, as you would expect. For McLaren, Mille produced the world’s lightest split-seconds chronograph with tourbillon in the shape of the ‘RM 50-03 Tourbillon Split Seconds Chronograph Ultralight McLaren F1’, while Ferrari was given the ‘RM UP-01 Ferrari’, currently the thinnest watch in the world, measuring a mere 1.75mm in height. Not content with that, Mille also has official partnership deals with several drivers as well, including Fernando Alonso, Romain Grosjean, Kiki Raikönnen, Charles Leclerc and Mick Schumacher.

Elsewhere, IWC has enjoyed a decade-long association with Lewis Hamilton which recently produced their third collaboration and the first designed by the driver himself. The IWC Portugieser Tourbillon Rétrograde Lewis Hamilton is a limited edition restricted to only 44 units—Hamilton’s race number—in platinum with a dial and fabric strap in the teal colouring of his Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 car. The team is sponsored by IWC too. Similarly, Girard-Perregaux have Aston Martin, TAG Heuer is at Red Bull and the whole thing is still looked after by Rolex as Global Partner and Official Timepiece.

A 2022 IWC Pilot's Watch Chronograph 41 Edition "Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula One Team" which sold on Watch Collecting in March 2023 for £5,400.

Elite watch manufactures and motor racing have long enjoyed an extremely robust bond. Each relies on near unfathomable levels of technical precision, and both project an aura of high-flying, dazzling affluence. There seems to be no slowing down in the affiliation either, treating us all to evermore impressive watches.

Watch Collecting's Motorsport Collection is running throughout the month of February, and you can view all of the watches here.

Have your say!